One of the criticisms sometimes leveled at my Nile series is that because the Ptolemaic Dynasty considered itself Macedonian, the emphasis I place on Egyptian culture–and Cleopatra Selene’s awareness of it–is somehow historically inaccurate or anachronistic.

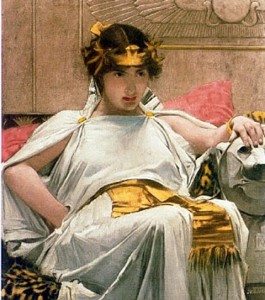

I believe this criticism is made primarily by people who correctly understand that Cleopatra the Great, Selene’s mother, was not a black African queen in the tradition of the incredibly awesome Kandake of Meroe. And by people who also correctly surmise that Cleopatra the Great is unlikely to have appeared to her subjects wearing exotic Old Kingdom garb in the fashion of Elizabeth Taylor in the Hollywood movie.

But to attempt to disassociate Cleopatra VII and her children from the Egyptian kingdom they ruled is to overlook a great deal of historical evidence. First of all, to characterize a woman whose family had not only lived in Egypt for nearly three hundred years, but ruled over it all that time, as somehow not Egyptian strikes me as absurd. (Pity poor Americans who identify as such with so much less history.) But even if one were to grant the argument that the Ptolemaic Dynasty held themselves apart from the subjects over which they ruled (because they did), that trend took an abrupt turn with Cleopatra the Great, who took affirmative steps to identify as Egyptian.

Cleopatra Selene’s mother was the first in her line to learn the native language. She identified herself not simply as philopater (lover of her father) but as philopatris (lover of her nation). She participated in native Egyptian religious rituals and had herself carved in relief in the old Egyptian style at Dendera. There is a remote chance, as explored in Professor Duane Roller’s excellent biography, that Cleopatra the Great herself may have had some small admixture of native Egyptian blood in her heritage. And even if she did not, evidence exists that Cleopatra Selene herself had a dearly loved cousin, Petubastes, who was half Ptolemaic and half of the native Egyptian priestly caste. (Roller, Cleopatra: A Biography, p. 166).

The fact was, times were changing, and Selene spent her childhood in a war-torn court where a national identity as Egyptians was important as it had never been important before. Her mother called upon Egypt to help her in her fight against Octavian’s Roman forces, and sought out Eastern allies even over more obvious Macedonian-Greek ones. While Cleopatra the Great certainly portrayed herself on coins as a Hellenistic queen, she was not averse to costuming, whether it was to portray herself as Venus, or Isis, or a pharaoh…an Egyptian title that she wanted, and took, for herself. Selene’s mother was, in short, a woman who always remembered her audience, and appeared as would most benefit her under the circumstances.

All this means that Selene did not grow up in a Macedonian bubble. The influences that show themselves in the city Selene built and coins she minted are a carefully cultivated mix of Macedonian-Greek and Egyptian.

There can be no question that Cleopatra Selene identified strongly with her Macedonian heritage. That she would have considered herself a champion of Hellenism. That she was desperate to maintain her tie to a dynasty that went back to the days of Alexander the Great and claimed kinship to him. All of that is in the books.

But so too did Cleopatra Selene see herself as the Queen of Egypt in exile.

Reasonable people can debate the extent to which Cleopatra Selene may have personally identified with the Egyptians, their religion, and their motifs. But there is no question that she did.

If that had been something I made up for the books, I would have acknowledged it as such in the author’s notes at the end.

AMEN, sister!

Glad to hear you chime in!

All I know is, you can go into all these detailed historical descriptions of Cleopatra all day long, and I will listen, completely fascinated. 🙂

Thank you! What a kind thing to say!

*slow clap* If I can’t call Cleopatra an Egyptian, then I can’t call myself an American. At that point in time the Ptolemies were no longer foreign invaders, they were legitimate kings and queens. They left their own Hellenistic mark on Egyptian culture while also becoming a part of the native culture.

By the way, have you ever read Joann Fletcher’s book Cleopatra the Great: The Woman Behind the Legend? She discusses Cleopatra’s Egyptian legacy in great detail.

I haven’t. It sounds like something I would enjoy very much, S.L.!

Really loved this. I was wondering though how was her father’s relationship with his native subjects that may have led him to take an Egyptian wife or wives? Could it be possible that Cleopatra’s mother came from the family of Petubastes? Didn’t the Ptolemies often had to court their native subjects during their family arguments…