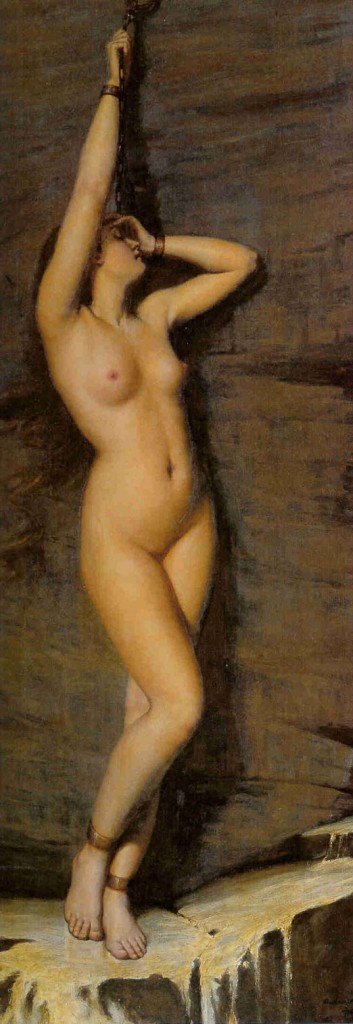

The heroine of my debut novel, Lily of the Nile, is Cleopatra’s daughter, the young Princess of Egypt who would be marched as a chained prisoner through the streets of Rome. At the end of a Roman triumph–that military parade during which generals celebrated their victories–their captives were often strangled or killed. There were, however, notable exceptions.

The heroine of my debut novel, Lily of the Nile, is Cleopatra’s daughter, the young Princess of Egypt who would be marched as a chained prisoner through the streets of Rome. At the end of a Roman triumph–that military parade during which generals celebrated their victories–their captives were often strangled or killed. There were, however, notable exceptions.

The children of royal families were sometimes spared from execution and kept as hostages to secure the submission of any remaining allies and ensure the good behavior of their conquered homelands. Such was the case with Cleopatra Selene, her twin Alexander Helios, and their younger brother Ptolemy Philadelphus. These three young children, the last survivors of the Ptolemaic dynasty, were not only spared, but taken into the household of Augustus to be reared by his sister.

Though hostage-taking was common enough in Rome even before Augustus came to power, it was this first emperor of Rome# who made a political art form of collecting the children of his enemies. Selene grew up amongst a houseful of children in what the French historian Auguste Bouche-Leclercq would call “the lamentable embassy of royal orphans.”

Some of these orphans were her own brothers and sisters, her father’s children by other wives. Iullus Antonius, the only one of Antony’s Roman sons to survive, probably last saw his father when he was seven years old and was formally brought into Augustus’ household when he was eleven. His mother died while he was still a toddler, so he likely had few memories of her. Augustus’ family may have been the only family that Iullus ever knew and he was granted extraordinary favors by the emperor–who gave his own niece Marcella to Iullus in marriage. (Still, a full-blooded heir of Antony was a dangerous man to leave alive, and this may have been Iullus’ undoing later in life.)

Another of the children Augustus collected for his political stratagems was Juba, son of a fierce Numidian king of the same name who chose the wrong side in a war against Rome and paid the price for it with his life. Juba was quite possibly an infant when his father was forced to suicide and no older than five years old when he was displayed in Caesar’s triumph. Unlike Selene, he would have no memories of his homeland nor siblings with whom to recount the tragedies of his young life. He was raised as a Roman boy and the family of Augustus was the only family he knew. Juba was a prodigy, recognized for his scholarship before the age of twenty. He served Augustus in a military capacity in Spain, and possibly before then in the war against Selene’s parents, and went on to become Selene’s husband and Rome’s most trusted client king.

Selene came to Rome in chains but left as a Queen and both she and her husband proved to be such fine examples of what could be accomplished by this policy of benign hostage-taking, that it would become a central hallmark of the Augustan Regime. Augustus would transform a boy named Hyginos who had been taken from Spain into his chief librarian. He would host the sons of King Herod so as to determine which of them might make a better heir for the troubled Judean kingdom. He would return a hostage prince to the Parthians in exchange for a peace treaty only to later host Parthian princes as guests, to indoctrinate them in the Roman way.

From our modern vantage point, there’s something decidedly sinister about using children in this way, and my novel examines the personal toll it might take on a little girl. But I must also point out that the policy was wildly successful and helped cement nearly a hundred years of relative peace that would come to be known as the Pax Romana.

You make history interesting!

I found your blog via a link in Beth Bernobich’s LJ. Looks like I got another link for my own blog sidebar. *grin*

We don’t know much about the childhood of Arminius, the Cheruscian prince who would lead the German tribes against three Roman legions in the battle of the Teutoburg Forest, but one theory says he was one of those child hostages. If so, Augustus went wrong with that one. 😉 Though personally I think it likely that he came into contact with Rome (maybe the city itself, but at least Roman culture in the Gallic provinces) as fugitive when a rival kicked his family out.

BTW, the Isis cult spread quite a bit through the empire; there are remains of an Isis temple under a shopping mall in Mainz/Germany. The place has been made into a little museum.

I’m afraid that most of my studies focused on the East. I’m woefully ignorant about the Germans except insofar as I know Augustus was devastated by the loss of his legions. If Arminius was a contemporary of Selene’s and one of the hostages there, I didn’t discover it. Is it possible he was one of the later generations of hostages, perhaps kept with the Parthian princes and Selene’s son, Ptolemy? I know there are some mysterious children on the Ara Pacis…do tell!

The problem is that his name doesn’t appear in the context of child hostages, so it must remain a guess. We do know that he was a citizen – Gaius Julius Arminius – and member of the equestrian order, cavalry praefect and most likely involved in the Pannonian War 6-8 AD before he returned to Germania. He also spoke educated Latin.

Rome made several attempts to conquer the German tribes. Drusus got there 12-9 BC; after his death Tiberius finished the campaign. Depending on what date one assumes for Arminius’ birth, he would have been 6 or 8 years at that time and in an age range for hostages. But we don’t know the exact conditions of the peace treaty with the Cherusci and other tribes; there surely was no complete conquest of the sort Augustus achieved in Aegypt. Hostages may have been an option, but not a certainity, moreover they would have to be mutual according to Germanic customs, and I doubt the Romans would go with that. Some tribes rebelled a few years later and Tiberius had to go back to put them to order; the last time that happened was in 6 AD, the time when Arminius obviously joined the Roman army. My guess (and the guess of Prof. G.A. Lehmann in Göttingen with whom I’ve studied) is that the Cheruscian nobility was at loggerheads and Arminius’ family had to flee – there is a brief mention of a failed attempt to restore a Cheruscian family to their rightful position – and the rebels against Rome were said rivals. Arminius then would have returned with Tiberius, got his father back on the ‘throne’ and stayed with the Roman army. Maybe out of gratitude, maybe he had no other choice because Tiberius wanted to make sure there won’t be another rebellion …. It’s a lot of guesswork, trying to figure out Tacitus’ cryptic remarks, and other fun.

But just the thing for a novelist. 🙂

Oh gosh, that’s a gold mine of a scenario right there. Gaius Julius Arminius? How else would he have had that name unless he was the child of freedman? That was the same kind of formula applied to Juba…Gaius Julius Juba. I’m hugely curious now.

If he was born in 18 BC that would make him of the same generation of Selene’s son. Why do I think I’ve read about him with regard to the Ara Pacis? Let me see if I can scare up the book.

Okay, I think this is the book in which I read some partial identifications of the child-hostages on the monument.

Oh, it gets even better. Arminius brother, who is only known by his agnomen Flavus, stayed faithful to Rome, became a centurion and fought on the side of Rome against his brother at the battle of Idistaviso in 16 AD. Flauvus\’ son he had with a princess of the Chatti, another German tribe, would later become king of the Cherusci under the name Italicus.

Arminius\’ wife Thusnelda and his infant son Thumelicus ended up in Roman captivity; Thumelicus died as gladiator in Ravenna. Thusnelda\’s father Segestes, probably the leader of the rival family that drove Arminus and his father Segimer out, fled to the Romans in 15 AD; or to be exact, Germanicus had to come with an army and get him out. 😉 He spent the rest of his life either in Italy or Gaul.

Also, you remind me that I need to start a page of links!

Thanks for the link to the book.

Heh, I forgot to check the No Spam Bot thingie and got some weird formatting in there as punishment. 🙂

So are you going to write about his childhood? If so, is your theory that he was raised in the household of Augustus? Will Ptolemy make an appearance? 😛 Not that I have a vested interest or anything…:P

No, I’m starting my novel A LAND UNCONQUERED a few month prior to the Varus battle, and it will then carry on to Germanicus’s campaigns 14-16 AD (can’t miss *two* pitched battles of Romans against Germans; I’m too much of a Bernard Conrwell fan for that 🙂 ). There may be some backstory about Arminius’ childhood, but I’ll most probably go with the fugitive variant. Arminius may have heard about Selene and Juba, though.

We know nothing about what motivated him to turn 180 degree and fight Rome. Taxes and Roman laws that suppressed the Germanic tribes is usually given as reason and while it may have played a role, I doubt it was Arminius’ sole motivation. I think the special treatment he received – member of the equestrian order, the position as praefect, which was more than other tribal leaders of auxiliary or numeri got – woke some ambitions to make a *Roman* career, and he found those hopes thwarted. Client king by the grace of Rome was the best he could achieve, and maybe that wasn’t enough for him. Either legatus Augusti pro praetore or some sort of High King of the Germans. He sorta told me so when I wrote a dialogue scene between him and Germanicus (before the Varus battle) that probably surprised both of us. 🙂 I usually rely on research and I’m a slow writer who edits a lot, but there are some rare moments when the writing flows and I feel like channelling a character, and this scene was one such.

Isn’t that great when that happens as a writer? It happens very rarely to me, but when it does, I take advantage of it. Good luck with it and I’m eager to read it when you’re finished.

Thank you. 🙂 If everything goes well, there may be a series of books, connected by a family feund of some fictive characters that carries the story further to the Batavian revolt and then to Scotland, to Mons Graupius and maybe the building of the Hadrian’s Wall. I got a folder full of notes and some scenes already.

Last year was the 2000 Year Anniversary of the Varus battle which has sprouted a veritable avalanche of new books and essays, a surprisingly large amount of them academic in nature, plus several exhibitions. I’m still sorting that material and the notes I took during Prof. Lehmann’s lectures and seminars. There will be a series of blogposts about the Romans in Germania when I’m done with that. Right now my blog has more posts about Medieaval castles and churches than Romans, but there’s some fun stuff in the archives. Nothing beats visiting the places where your novels take place – as far as those places still exit. It takes a bit of imagination. 😉