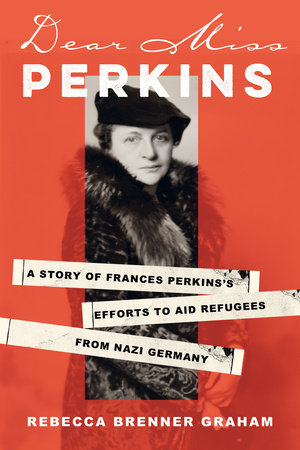

Dr. Graham did me the honor of providing this sneak peek of her work for my readers. I highly encourage you all to run out and grab this important book.

Introduction

by Rebecca Brenner Graham

On the night of November 9, 1938, Nazis burned synagogues, looted Jewish homes and businesses, raped Jewish women, and deported Jewish men to concentration camps across Germany and Austria. The Night of Broken Glass, Kristallnacht, made headlines around the world, including in the U.S. For many Jewish people, that night marked the first time that they truly wanted to leave their homes forever. For others, it increased their resolve to seek refuge.

In the U.S., the agency that might be able to help them—the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS)—was under the Department of Labor, which was headed by the first female cabinet secretary in American history, Frances Perkins. At age fifty-eight, she wore a tricorne hat and pearls. She was a white woman with dark eyes and dark, matronly clothing. Her handbag and heels stood out under the cabinet meeting table surrounded by men’s shoes. She slept in a single bed because her husband was in a psychiatric institution, but her personal life was off limits to anyone outside her miniscule private circle. Perkins habitually felt others’ pain as her own, and refugees were no exception.

She had a flurry of ideas, mostly good ones, all of which had been in motion before 1938. The ideal course of action would be expanding U.S. immigration quotas—the numerical caps that dictated how many people born in each country could immigrate per year—but because those numbers were controlled by Congress, that seemed unlikely. She proposed mortgaging quotas, combining both 1939 and 1940 allotments into 1939. She supported adding an additional quota for child refugees to offer children a chance at a safe life. If Congress would not adjust quotas, she suggested a separate quota for the American territory of Alaska to settle Jewish refugees there.

Could the U.S. be a refuge to oppressed people? Did it want to be? Could it overcome its own prejudices to be “the golden door”? All refugees whose lives were in danger counted as immigrants under the same quota laws as other foreigners seeking to relocate. Perkins had helped shepherd radical New Deal legislation—the Social Security Act of 1935, the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, and the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938—through Congress. Could she do the same with refugee policy? These questions kept her up at night.

The morning after Kristallnacht was the morning before Armistice Day on the twenty-year anniversary of the end of World War I. Americans listened to Kate Smith perform over the radio a new song composed by Irving Berlin to mark the occasion. The original first verse of the song, “God Bless America,” was “As the storm clouds gather, far across the sea / Let us swear allegiance to a land that’s free / Let us all be grateful that we’re far from there / As we raise our voices in a solemn prayer.” Musical tones from the accompanying instruments then bounced into a vivacious “God Bless America.” Let us all be grateful that we’re far from there as we raise our voices in a solemn prayer. As a devout Christian, Perkins was undoubtedly praying. But unlike most of the country and most of the government, she tried to translate those thoughts and prayers into actions.

At what point would rising Nazi atrocities awake the U.S. from its postwar isolationism? How might Americans care about the welfare of noncitizens, especially while struggling through the poverty and scarcity of the Great Depression? Contemporary myths of immigrants taking American jobs and resources date back to the 1930s, and farther. “I am a ratcatcher in Boston for 20 years. I can show you 500 alleys in Boston with 100 children ages 5 to 8 in these alleys . . . These children are in bad need of care. So, take care of kids at home first,” an American citizen wrote to Katherine Lenroot, head of the Children’s Bureau in Perkins’s Department of Labor, in 1939. The question of how to share resources with refugees when citizens lacked resources might have seemed well-meaning enough until he signed off, “Are you taking orders from . . . the Rich Jews?”

On November 18, 1938, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt announced via press conference his willingness to extend the tourist visas of 12,000 to 15,000 German-Jewish refugees already in the country. Perkins had the idea for these extensions in 1933.

Following a cabinet meeting in spring 1933, a State Department official journaled about a phone conversation in which the State Department had tried to explain immigration to the Labor Secretary. He wrote that Perkins “quite blew our poor Undersecretary off his end of the phone.” Perkins claimed that it was an American tradition to help people seeking asylum. By 1938, however, Perkins’s tone had shifted. “A great many people seem to hold the belief that there is some provision in the immigration laws for political refugees or for making this country an asylum for the oppressed of all nations. This is absolutely not the case,” she wrote to a correspondent.

Between those two different claims from Perkins, she’d come face-to-face with the antithesis of her highest American ideals when anti–New Dealers in Congress tried to impeach her. For her role in protecting an Australian immigrant and labor organizer, Harry Bridges, Perkins faced an impeachment hearing, hate mail, bad press, and even antisemitic slurs from conspiracy theorists claiming she was Jewish. She handled the accusations of Jewishness with grace, publicizing a letter expressing that she’d be proud of her Jewish heritage if she had it, which she didn’t. But overall, the impeachment experience shook her.

Nevertheless, she persisted. Through a combination of relaxing visa requirements, reducing deportation numbers, devising the corporate affidavit for businesses to finance refugees, and collaborating with the German-Jewish Children’s Aid Inc. on a robust child refugees’ program, Perkins contributed to saving the lives of tens of thousands of refugees from Nazism.

By the time initiatives that she’d set in motion reached Congress, however, any political capital that she once had was in shambles because of the impeachment ordeal. These efforts to accept refugee children and create a German-Jewish settler colony in Alaska failed in 1939 and 1940, respectively. Both ideas crossed Perkins’s mind and materialized in scribbles on notepaper across her desk. The Alaska plan signified a rare instance when American colonization and imperialism could not prevail above all else because the antisemitism toward those who would be settling was too strong.

Perkins navigated an American climate of antisemitism, capitalism, misogyny, xenophobia, and more. Her positionality as a Christian, educated, relatively privileged descendant of English settlers made her encounters even more unsettling and stark. As a historical figure, she’s a unique tour guide for contemporary readers interested in the history of the U.S. in the 1930s. As an American governmental official, she offers the lens into American responses to the German-Jewish refugee crisis prior to World War II. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt later moved the INS from Labor to Justice in 1940 ahead of America’s entrance into World War II—because Perkins’s immigration policies were too progressive.

This story is easy to miss. Myths have persisted to obscure it for too long. Sixty years after her death, Perkins continues to be relatively unknown. Keeping a low profile was partially her own doing, and the men who wrote first and second drafts of history through journalism and scholarship didn’t need to be asked twice to downplay her role. Further, ideas about American immigration history are still recovering from the “melting pot” myth of American cohesion and happiness. And that leaves historical memory of Nazism and the Holocaust in the American collective consciousness, which has taken a tumultuous journey all by itself. Uses and abuses of Holocaust memory in fiction, politics, and more are endless. As a result, the first female cabinet secretary—a quirky fun fact—the U.S. as a nation of immigrants, and American moralistic outrage and resolve to “never forget” and “never again” might seem like three separate strands of history. In truth, they converge in a singular story.

This looks like a very interesting book. Thank you for giving me the chance to win it.

This book sounds fascinating! I’ve become a big admirer of Perkins since reading Becoming Madam Secretary.

Wow this book sounds really good. I enjoy learning all I can about history. Shall we never forget so that we don’t repeat.

This books looks very interesting!

It’s such a shame that accomplished women remain relatively unknown to history. I appreciate their stories being told.

Frances Perkins was an amazing woman. I always knew she was the first female Cabinet Secretary, but I don’t know her whole story. I can’t wait to learn more about her.

Interesting book. Like to read about real life events in history.

I have previously read some about France’s Perkins and find her story very interesting.

Becoming Madam Secretary is at the top of my all time favorite books, so I am anxious to learn more about Frances Perkins.Something amazing happened yesterday when my husband and I went out to lunch ! Sitting behind me were two men talking about historical books. Sorry to eavesdrop but when the name Frances Perkins came up,I couldn’t help but listen. Their comments on Becoming Madam Secretary were highly complimentary. As I was leaving, I acknowledged listening to their conversation. They were thrilled to meet another Frances Perkins fan !

Thank you for this extra opportunity to win this book. ??

I can’t wait to read and learn about this amazing woman!

Francis Perkins is such a fascinating woman, way ahead of her time!

Oh this sounds like a wonderful read

Sounds like a grand book.

And now from INS to ICE,how did it go so wrong? Too many immigrants.

Frances Perkins is one of my heroes!

This book sounds so good. Have been reading a lot of books around that era

I’m excited to learn more about her. I’ve been reading a little about Eleanor Rossevelt lately.

Wow, thank you so much, I enjoyed learning about the amazing Frances Perkins?. Your book “Becoming Madam Secretary” was wonderful. Perkins did so much for this country, she with President Roosevelt changed the lives of us all.

I just ordered this book after just finishing becoming Madam Secretary.

Wow, I love learning about WWII!

I’ve read only 1 book concerned with Jewish refugees trying to enter the U.S and was very disappointed that the U.S. wasn’t more helpful. I would love to read this story.

Loved learning about FranceS Perkins and would love to read this book!

I would love to win this book. She was a hero!

Sounds like a really good read

I’m excited to get to know more about Frances Perkins and look forward to this book.

this looks great

Looking forward to reading this and learning more about Frances.

I woud love the chance to read this book about Frances Perkins!

Why don’t we hear about this amazing woman in history classes? I loved Becoming Madam Secretary. I was a history major in college and yet never heard about her. Of course this was way back in the 1960s. When DOGE was busy, eliminating things in Washington I noticed Francine’s name on one of the buildings. If she has her name on a building, she certainly deserves to be known why! I am going to recommend this book at my next book club meeting. I would love to win this prize.

As a history buff, I love reading about Frances Perkins and the significant impact she had on the USA’s evolution.

Never heard of Frances before, but I would love to learn more about her.

I always hope I would do the right thing in this tripe of scenario, but I’m also afraid I wouldn’t be brave enough if it out my loved ones I. Danger.

Thank you for the chance and have a lovely summer.

I have recommended this pair of books over and over again! They are a perfect set!

I would like to read this book

I love all things WWII and especially when it is told to me from a unique POV. This book seems to be exactly what I would love!

This woman sounds absolutely amazing.

A remarkable woman. The books sounds wonderful.

Thank you for the opportunity to win.

Chance to win!

This book sounds fascinating and informative.

This sounds amazing!

I’d love to win Dr. Graham’s book on Frances Perkins. In 2001 I had the role of Secretary of Labor, Frances Perkins, in the musical production of “Annie” at the Duluth Playhouse. It was a small part but each night I felt honored to have the privilege of portraying the amazing woman who was the first woman in history to be a member of the U.S. Presiident’s Cabinet.

Francis Perkins was a wonderful woman who was able to implement so many positive programs and policies. We need to know more about her and hope that the current administration learns from her example.

I love Frances Perkins. I read Becoming Madame Secretary by Stephanie Dray and I have become a big fan of all the things Frances Perkins accomplished in her lifetime. Wow — Just Wow! I would love to read and own a new book about her. Thanks for the opportunity.

This sounds like a great sequel to Becoming Madam Secretary, Stephanie Dray’s book about Frances Perkins ends in 1935 and does not include the years during WW2.

This sounds like a really great read!